ECCE HOMO TESCO

DOYLE & MALLINSON

26 June - 25 July, 2010TEXT

Behold the Tesco Man...

by Peter Bonnell

In 1891 the Dutch anatomist and sometime surgeon, anthropologist and paleontologist Eugene Dubois discovered an epoch-defining archaeological find named Pithecanthropus erectus. Loosely translated as “ape-human which stood upright” and known around the world as ‘Java Man’, Dubois’ discovery of a fragment of skull and a solitary leg bone served, amongst other claims, to add weight to Charles Darwin’s Theory of Evolution.

Continuing debates within the scientific community challenge Dubois’ discovery, particularly with regards to its true classification and origins (it has since been re-named Homo erectus, an early hominid), with some evolutionists still firmly convinced it is evidence for their holy grail: the missing link. Missing links, superstition and long-held beliefs provide the basis for the playfully anarchic work of Shaun Doyle and Mally Mallinson; for them the fact that a missing link would provoke and challenge the creationist theory that the Earth was created approximately 6000 years ago is manna from an illusory heaven. Doyle and Mallinson unearth and expose the contradictory and inflammatory tenets inherent to the main world religions with a gleeful relish mixed with pitch-black humour. In fact, they often tread a fine line that at times could see them the target of retaliatory attacks by religious extremists, particularly when considering their installation The Garden Centre of Gethsemane (2006), complete with a Christ figure, situated in an inflatable paddling pool, with eyes gushing blood.

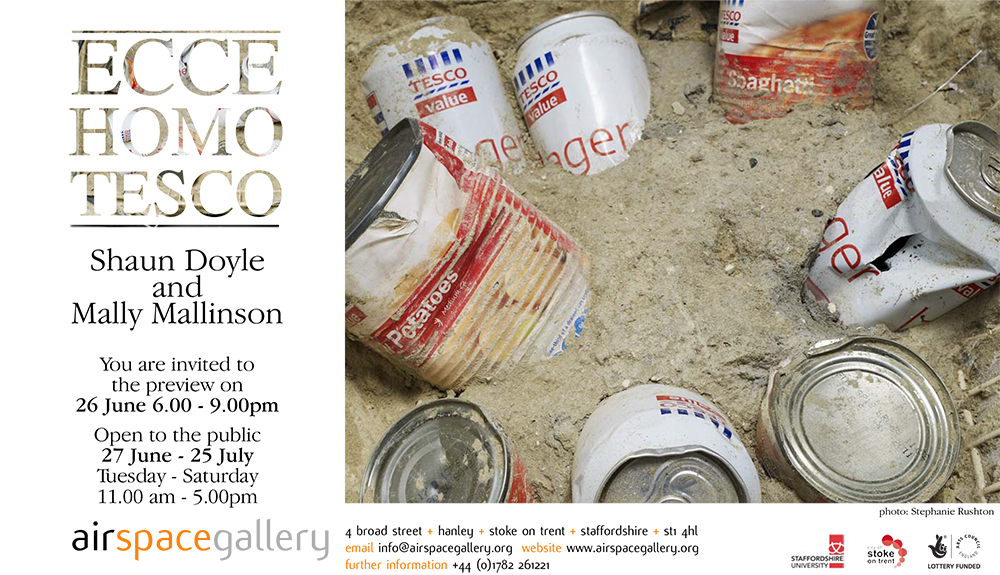

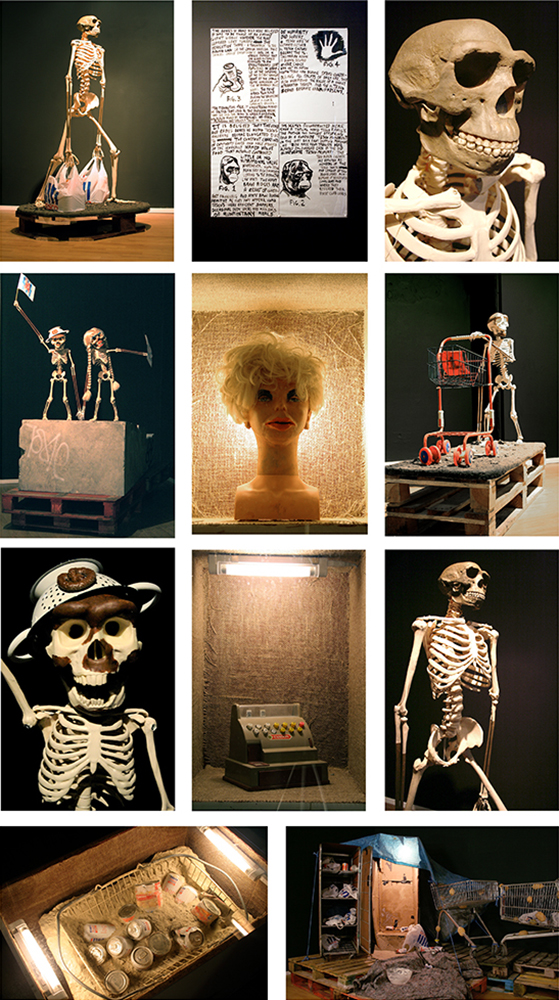

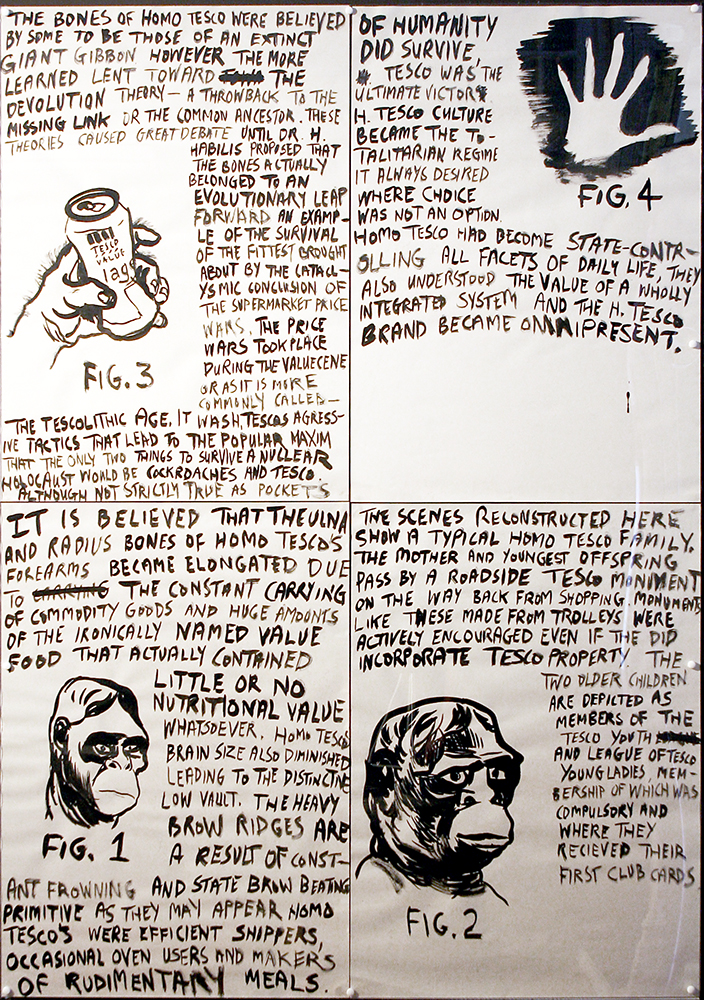

Doyle and Mallinson also examine elements of society that are overlooked, or perhaps should remain overlooked. King Tat (2005), for example, was presented as a deadpan archaeological find of a newly excavated tomb not of an Egyptian King, but a down-at-heel forgotten member of society whose worldly possessions could be considered the height of working class taste. Tat himself was entombed in a decrepit chest freezer in an antechamber of his flat surrounded by graffiti-styled frescos, celebrating nothing except the futility inherent for many in early twenty-first century life. The artists had previously worked in museums creating dioramas, skills they utilized in constructing King Tat. It is with their latest work, Ecce Homo Tesco (2009), that they again present a range of horribly convincing and uncomfortably satirical dioramas that are a conflation of contemporary concerns and debates. Referencing Dubois’ discovery, Doyle and Mallinson’s recently discovered Ecce Homo Tesco, (or Tesco Man as Java Man) is an Ecce Homo for modern times. Religious doctrine again creeps in: “Ecce Homo”, or “Behold the man” was coined by Pontius Pilate as he presented Christ to the crowd prior to His crucifixion. Tesco Man is not just an innately humorous riposte at religion, but also a character strangely loaded with pathos, a mirror of society and our times: “Behold the lazy, track-suited lager-swilling man.”

Ecce Homo Tesco also explores one potent and contentious legacy of Dubois’ discovery: the Piltdown Man hoax of 1912. The very existence and subsequent debunking of Piltdown Man provides an argument for creationists who point to it as an example of the uncertainty and guesswork surrounding archaeological research into early mankind. One photograph included in Doyle and Mallinson’s exhibition at Airspace Gallery is an image of Tesco Man – a hairy ape-like figure with disconcertingly elongated arms stretched by the perpetual carrying of two bags of Tesco shopping – confronting the camera as if surprised. This image, and another that captures him shrouded by trees in a rubbish strewn wasteland, is eerily reminiscent of the footage of Bigfoot shot by Roger Patterson and Robert Gimlin on the 21st of October, 1967 in Bluff Creek, California. Doyle and Mallinson’s discovery that the plural of the Latin term ‘tescum’ (an obvious play on Tesco) is ‘tesci’, and can be loosely translated as ‘wastes’ or ‘wasteland’, is highly ironic as the Airspace Gallery is situated adjacent to a parcel of land recently purchased by Tesco. The environment in which Tesco Man lurks is considerably less salubrious than Bigfoot’s squeaky-clean Golden State.

Questions and strategies of veracity, linked to those surrounding Dubois’ discovery, are deliberate ploys in Doyle and Mallinson’s work. Artefacts included in Ecce Homo Tesco: the petrified remains of Tesco Man’s hairy arm clutching a can of Tesco own brand lager; a skeleton with elongated arms holding the handle of a supermarket trolley, and the Pompeii-like remains of a shopping basket of partially entombed cans of lager, are convincing in that they allude to a form of taxonomic classification. The petrified arm is photographed with a black and white measuring device; other artefacts – such as a series of vicious looking clubs – are photographed in a similar fashion. These allusions to museum standard systems of classification both debunk and at the same time provide evidence for Tesco Man’s existence, mirroring dialectical arguments inherent in the battle between science and creationism.

Ecce Homo Tesco is a confluence of numerous theories and extrapolations – part anti-religious rant, part scientific debunking, concerned with the need by human beings to collect things and display them. Regardless of the veracity of Doyle and Mallinson’s artefacts, they celebrate naïve small town museum dioramas and heroically bad papier-mâché models that bear no resemblance to actual events they are meant to depict. Doyle and Mallinson’s works embody a keen observance of the absurdity of life and the world around us, and their down-at-heel Tesco Man, and the remains found with him, critiques a national (and perhaps irrational) desire to shop and consume. Their work is particularly prescient in terms of global warming and daily media predictions of doom and Extinction Level catastrophe for the human race. Ecce Homo Tesco alludes to paranoia as supermarket price war, but perhaps also to continually escalating conflicts blighting every corner of the world. With escalating paranoia, and North Korea and Iran allegedly soon to have, or already having, possession of the bomb, the question ultimately becomes three-fold: how long do we have left, what will be our legacy, and most pertinent of all: will archaeologists of the distant future come to conclude that we were all a race of long-armed monkey men?

Peter Bonnell is Curator of Exhibitions and Education at ArtSway